Lost at Sea

Just two years after the world was shocked by the sinking of the Titanic, another passenger ship sank in Canadian waters with an even greater loss of life, yet few have heard the tragic tale. Until now.

Prefer to listen? Listen to this article in the player below:

Word spread quickly through the small town that a ship had gone down and survivors were being brought ashore. With a working waterfront on the St. Lawrence River, Rimouski, Quebec, has known its share of lost seamen, but in the still-dark hours of a quiet spring morning, no one could have imagined it was the Empress that had sunk in the river’s cold water.

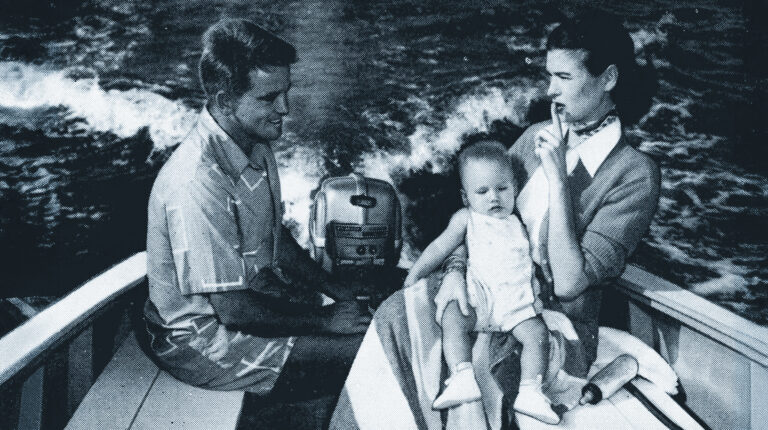

The Empress of Ireland was the pride of the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company. Built in Glasgow, Scotland, the Empresmade its maiden voyage from Liverpool, England, to Quebec in June of 1906. For the next eight years, it would safely carry tens of thousands of passengers across the Atlantic between Canada and the United Kingdom. Young and old alike sailed to the new country in search of adventure or a fresh start. Families having established themselves in the Americas also frequently booked return passages to the U.K. to show loved ones back home their newfound success and newly born grandchildren.

The Empress was not a grand luxury liner in the class of the Titanic, Olympia or Britannic, but at 551 feet long it was respectable in size and appointments. The Empress was operated by a relatively small crew of 373 and could accommodate 1,542 passengers in four class sections on seven decks. The Empress was built to serve working-class families, with a fortunate few in the relative luxury of a small first-class section.

At 4:27 p.m. on the afternoon of May 28th, 1914, the Empress disembarked Quebec City for a six-day voyage to Liverpool, England, the first two days of which were to be on the St. Lawrence River. A seasoned ship at this point, it was setting out on its 96th voyage. It was a pleasant spring day on the river as Capt. Henry Kendall gave orders to release the lines. This was a day Capt. Kendall worked his whole life to achieve. Having risen through the ranks, this was to be his first voyage as master of his own ship. Little did he know what fate held in store for him.

Passengers milled about in the long daylight hours, learning their way around the ship. Parents allowed children to roam freely. Diners enjoyed the late sunset and fresh air in after-dinner strolls on deck. As night closed in, passengers and crew settled in for a calm first night underway.

Like most inland bodies of water that receive ship traffic, the St. Lawrence River requires pilots to operate from the bridge of a ship, directing the helmsman through the local waters. Bay and river pilots are specially trained in the local conditions of their area. On the St. Lawrence River, pilots are taken on and offloaded at Point-au-Père, Quebec, near Rimouski. Point-au-Père, on the southern shore of the river, is easily identifiable by its well-known lighthouse. With the lighthouse in sight, ships would steer a course close to shore to rendezvous with a small pilot boat for the transfer. One of the Empress’s last tasks that night before heading into the open water of the Gulf of St. Lawrence was to disembark its pilot.

Also on the river that evening was the Norwegian collier Storstad. Inbound from Sidney, Nova Scotia, and chartered by the Dominion Coal Company, the Storstad was carrying a load of the black rock to Montreal. It was to spend the summer months moving coal up and down the river.

Close to 2 a.m. on the morning of May 29th, the Empress and Storstad sighted each other near Point-au-Père. Capt. Kendall, on the bridge of the Empress, saw the Storstad off his port bow. If Kendall held this course, the ships would pass each other port to port, but it would take the Empress close to shore and off his intended course. Kendall estimated the Storstad to be approximately 8 miles away; more than enough time, he thought, for a turn to port, and he set his course for open water. On this course, the Empress would cross the Storstad’s bow, and the two ships should safely pass starboard to starboard while still miles apart. In late spring, the warm, moist air above the cold river water can produce a fog so dense, visibility nears zero. Shortly after Kendall laid in his new course, a spring fog enveloped both ships.

Concerned he could no longer trust his prior understanding of each ships’ position, Kendall gave an order to slow his ship but kept it on course. The Storstad, not realizing the Empress intended a starboard-to-starboard passing, was also concerned with their proximity to each other. Believing they were passing port to port, the Storstad turned more to starboard, unknowingly taking it directly into the Empress’s path. Minutes later, the two ships came into view of each other, now on a collision course. It was too late to stop it. The Storstad’s bow cleaved the Empress well below the waterline, leaving a gaping hole 16 feet wide. Sixty thousand gallons of water per second began pouring through the opening as the river’s current and the Storstad’s momentum pulled it away from the doomed Empress. The list to starboard was immediate, with the submerged pressure forcing even more water into the opening. The Empress had watertight doors dividing sections below decks, but they required manual operation; the water coming in overwhelmed the crew so quickly, they had no time to seal them. Many passengers also had port holes open for the fresh cool breeze, allowing cabins to flood when the port holes reached the water. If there was any mercy for the passengers and crew lost in this tragedy, it was that their demise came quickly: The horror for all aboard lasted a mere 14 minutes before the Empress slipped beneath the waves.

Comparisons to the Titanic were inevitable, but there is no victory in winning this game of numbers. The Titanic took 2 hours and 40 minutes to sink; the Empress went down in a remarkably short 14 minutes. The Titanic lost 832 passengers and 635 crew; the Empress lost 840 passengers and 172 crew. An unspeakably sad statistic was that only four children of the 138 on board the Empress survived the sinking. The ship went down so fast, there was no time to follow the tradition of women and children first. Also aboard were 170 members of a Salvation Army band, on their way to an orchestral convention in London. All perished. Following new safety regulations implemented after the sinking of the Titanic, the Empress was equipped with enough lifeboats for all passengers and crew; however, with the immediate and severe list to starboard, only a few of the ship’s lifeboats were launched. In total, of the 1,477 passengers on board, only 465 survived.

Of the survivors, no one could blame a young William Clark for giving up the adventurous life at sea following the accident. Working as a fireman aboard the Empress, Clark was in the engine room stoking the steam engine’s fires when the Storstad struck the ocean liner. Clarke recalled later that he had no memory of getting to his lifeboat station. However, the events of that night were all too familiar to Clark, as he worked in the same capacity on the Titanic’s maiden voyage, having survived that historic sinking as well.

The Storstad, with only minor damage to its bow, joined rescue ships from Rimouski. The few survivors able to withstand the frigid waters were taken to Rimouski, where many later died of pneumonia. The Storstad continued its journey to Montreal. Following the sinking, from mid-June through mid-August, numerous dives were made to retrieve bodies and valuables from the ship. The last dive was made on August 20th, bringing up the purser’s safe. Unfortunately, only a small number of bodies were retrieved, with many trapped beyond the divers’ reach within the wreck.

Certain events in history have a way of burning themselves into our collective memory. Often due to the horrific nature, we are fascinated by their stories. While as great of a tragedy as the Titanic, the sinking of the Empress never garnered the press nor attention the Titanic received. Soon after the Empress sank, the world’s attention was drawn to the early beginnings of World War I, leaving the story and memory of the ship lying silent beneath the waves with the vessel and precious lives lost.

The Empress would lie in its watery grave for another 50 years before it was discovered by scuba divers in 1964. Lying in only 130 feet of water, the wreck is reachable on open-circuit scuba equipment. Recreational divers started visiting the wreck frequently. In various times and places throughout history, salvage has been a respectable endeavor. Key West, Florida, and much of North Carolina’s Outer Banks were built from salvaging ships wrecked on nearby reefs. Be that as it may, salvaging pieces from a wreck still holding the remains of lost souls feels unconscionable. Unfortunately, divers continued to explore the wreck until 1998, when the sunken liner was classified as a historic site by the Quebec government, protecting it from any further plundering.

Kendall survived the sinking and was rescued from a lifeboat with other crew and passengers. Following an investigation into the accident, he was cleared of all charges in the disaster. He went on to serve aboard other ships and pursued a long life at sea. He passed away quietly in a nursing home in 1965 at the age of 91. His obituary in The London Times made no mention of the sinking of the Empress of Ireland.

A monument inscribed with the names of those lost on the Empress stands over a mass grave on a coastal road near Pointe-au-Père in Rimouski. The monument asks all to remember Canada’s greatest peacetime maritime disaster.

The Pointe-au-Père Maritime Historic Site has over 200 artifacts from the wreck, period photos, accounts by passengers and their descendants, as well as models of the ships. Ships passing will see in the river a buoy which permanently marks the location of the wreck.